These tutorials address an older version of D3 (3.x) and will no longer be updated. See my book Interactive Data Visualization for the Web, 2nd Ed. to learn all about the current version of D3 (4.x).

What is binding, and why would I want to do it to my data?

Data visualization is a process of mapping data to visuals. Data in, visual properties out. Maybe bigger numbers make taller bars, or special categories trigger brighter colors. The mapping rules are up to you.

With D3, we bind our data input values to elements in the DOM. Binding is like “attaching” or associating data to specific elements, so that later you can reference those values to apply mapping rules. Without the binding step, we have a bunch of data-less, un-mappable DOM elements. No one wants that.

In a Bind

We use D3’s selection.data() method to bind data to DOM elements. But there are two things we need in place first, before we can bind data:

- The data

- A selection of DOM elements

Let’s tackle these one at a time.

Data

D3 is smart about handling different kinds of data, so it will accept practically any array of numbers, strings, or objects (themselves containing other arrays or key/value pairs). It can handle JSON (and GeoJSON) gracefully, and even has a built-in method to help you load in CSV files.

But to keep things simple, for now we will start with a boring array of numbers. Here is our sample data set:

var dataset = [ 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 ];Please Make Your Selection

First, you need to decide what to select. That is, what elements will your data be associated with? Again, let’s keep it super simple and say that we want to make a new paragraph for each value in the data set. So you might imagine something like this would be helpful

d3.select("body").selectAll("p")and you’d be right, but there’s a catch: The paragraphs we want to select don’t exist yet. And this gets at one of the most common points of confusion with D3: How can we select elements that don’t yet exist? Bear with me, as the answer may require bending your mind a bit.

The answer lies with enter(), a truly magical method. Here’s our final code for this example, which I’ll explain:

d3.select("body").selectAll("p")

.data(dataset)

.enter()

.append("p")

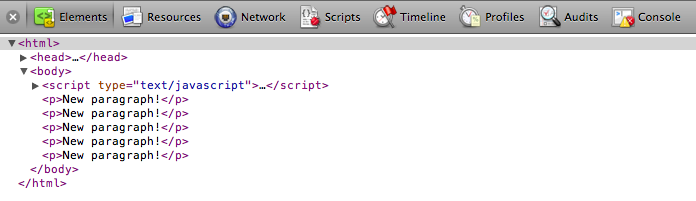

.text("New paragraph!");Now look at what that code does on this demo page. You see five new paragraphs, each with the same content. Here’s what’s happening.

d3.select("body") — Finds the body in the DOM and hands a reference off to the next step in the chain.

.selectAll("p") — Selects all paragraphs in the DOM. Since none exist yet, this returns an empty selection. Think of this empty selection as representing the paragraphs that will soon exist.

.data(dataset) — Counts and parses our data values. There are five values in our data set, so everything past this point is executed five times, once for each value.

.enter() — To create new, data-bound elements, you must use enter(). This method looks at the DOM, and then at the data being handed to it. If there are more data values than corresponding DOM elements, then enter() creates a new placeholder element on which you may work your magic. It then hands off a reference to this new placeholder to the next step in the chain.

.append("p") — Takes the placeholder selection created by enter() and inserts a p element into the DOM. Hooray! Then it hands off a reference to the element it just created to the next step in the chain.

.text("New paragraph!") — Takes the reference to the newly created p and inserts a text value.

Bound and Determined

All right! Our data has been read, parsed, and bound to new p elements that we created in the DOM. Don’t believe me? Head back to the demo page and whip out your web inspector.

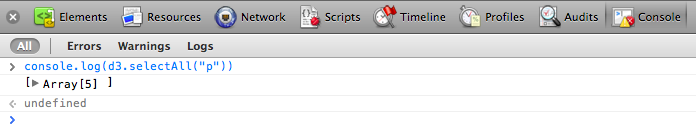

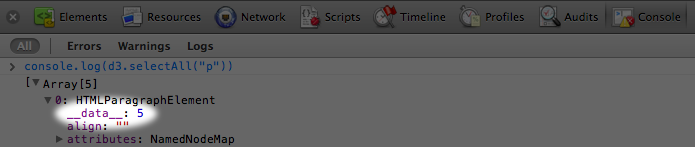

Okay, I see five paragraphs, but where’s the data? Click on Console, type in the following JavaScript/D3 code, and hit enter:

console.log(d3.selectAll("p"))

An array! Click the small, gray disclosure triangle to reveal more:

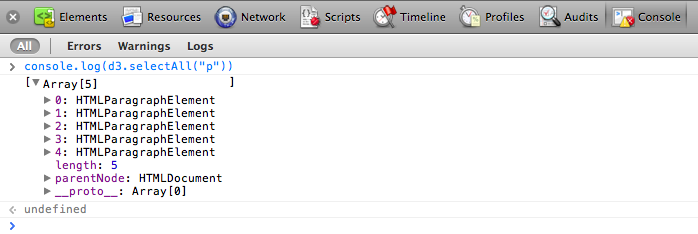

You’ll notice the five HTMLParagraphElements, numbered 0 through 4. Click the disclosure triangle next to the first one (number zero).

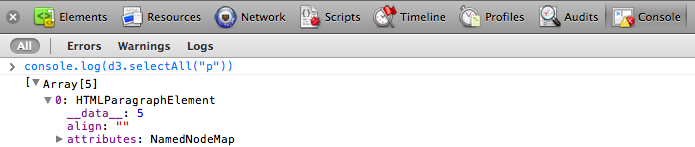

See it? Do you see it? I can barely contain myself. There it is:

Our first data value, the number 5, is showing up under the first paragraph’s __data__ attribute. Click into the other paragraph elements, and you’ll see they also contain __data__ values: 10, 15, 20, and 25, just as we specified.

You see, when D3 binds data to an element, that data doesn’t exist in the DOM, but it does exist in memory as a __data__ attribute of that element. And the console is where you can go to confirm whether or not your data was bound as expected.

The data is ready. Let’s do something with it.

Next up: Using your data →

These tutorials address an older version of D3 (3.x). See my book Interactive Data Visualization for the Web, 2nd Ed. to learn all about the current version of D3 (4.x).

These tutorials address an older version of D3 (3.x). See my book Interactive Data Visualization for the Web, 2nd Ed. to learn all about the current version of D3 (4.x).

Download the sample code files and sign up to receive updates by email. Follow me on Twitter for other updates.

These tutorials have been generously translated to Catalan (Català) by Joan Prim, Chinese (简体中文) by Wentao Wang, French (Français) by Sylvain Kieffer, Japanese (日本語版) by Hideharu Sakai, Russian (русский) by Sergey Ivanov, and Spanish (Español) by Gabriel Coch.